The article was first published on The Ousia Review

By Katerina Pampouki*

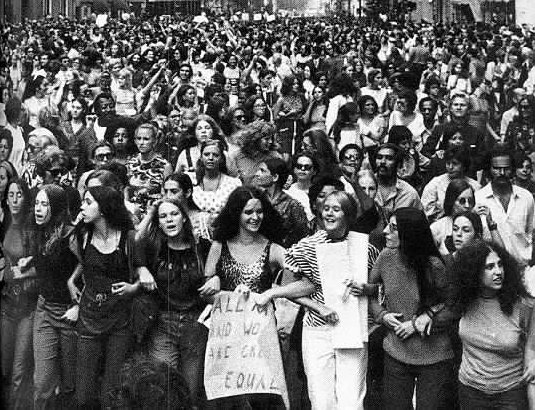

Women are often told to “find their voice”. Women do not need to “find” their voice – they have always had a voice. Rather, women need a safe environment to use it. And when they do, we need to listen.

Greek Olympic gold medalist Sofia Bekatorou recently spoke out about an alleged sexual assault by a high-ranking official of the Hellenic Sailing Federation. Although her claim was ultimately held to be time-barred, her action carries great symbolic importance: Bekatorou broke the long-standing silence in Greek society surrounding sexual harassment and assault. The practical implications are also monumental, as many women have now followed her steps, bringing, even if belatedly, a #MeToo-like movement to Greece. This has sparked heated debate and has caused (alleged) perpetrators to be publicly condemned. Such public outcry can be seen as reviving ostracism, the prime method of punishment used in Ancient Athens.

The issue raises interesting legal questions and prompts a much-needed evaluation of the current legal framework. Yet, the power of such a movement is its potential for social change. Currently, Greek society seems torn. Unsurprisingly, many are criticizing the women who are speaking out, blaming them and claiming that they should have spoken sooner. At the same time, others are applauding the women for their bravery and courage to demand justice. The aim of this article is not to engage in criticism of either of the sides of the debate, but rather to point out how the ongoing public discussion of harassment on the basis of sex is evidence that the lack of visibility in Greece is changing. Hopefully, the dialogue that seems to be unfolding will be a constructive one, bringing a breath of fresh air to the social and legal structures of Greece.

First of all, sexual harassment in the workplace is inherently a gendered phenomenon because it disproportionately affects women. Sexual harassment is inextricably linked to abuse of power, hence its frequent appearance in the workplace, notably in the art industries. As eloquently put by Montesquieu, “every man who has power is impelled to abuse it; he goes on till he is pulled up by some limits”. This is where law should come in. Limits are needed. It is imperative that there is a proper legal framework standing as a strong backbone to all social relationships, especially between employers and employees.

Unfortunately, the current framework is far from “proper”. The most important and indeed fatal weakness of the law is its failure to incorporate an independent, separate provision for sexual harassment. The current provision dealing with sexual harassment is merely attached as an “extenuating circumstance” to Article 337 of the Greek Penal Code. This is simply not enough. As a broadly worded provision addressing crimes against sexual dignity, Article 337 leaves potential victims in a feeble legal position. The vague words of the provision establish a dubious threshold which cannot be reached with certainty. A precise and detailed definition of sexual harassment is needed to promote a shared understanding of its exact meaning and more specifically to succeed in guiding those who are unsure about whether they can file a claim or not. This omission in the Greek criminal law system is shocking given that most other European countries, including France, Britain and Bulgaria adopted provisions that directly prohibit harassment in the workplace back in the 1990s. The criminal law primarily serves a protective function. However, the Greek Penal Code seems to be terribly lacking in this respect; instead, it provides shelter to people (more often than not, men) in high-ranking positions, allowing them to commit crimes without any regard to the consequences. The new scandal with Lignadis, the former Director of the Greek National Theatre who has been accused of pedophilia and raping minors on many occasions portrays abuse of power and institutional corruption in all their glory. Now, more than ever, the need for transparency is clear: the effective sanctioning of criminal phenomena requires victims to be given their right to denounce; the risk of leaving such voices going unheard is too serious to ignore.

Furthermore, it is regrettable that the progressive EU framework has left the domestic regime almost untouched. In fact, the gaps in the legal system trace back to the 2002 Government’s failure to appropriately transpose Directive 2002/73/EC which aimed at achieving equal treatment for men and women in relation to aspects of employment. Of course, this mistake should not be seen as attributed to the specific Government; Greece has a history of being exceptionally ineffective when it comes to administrative matters.

Kyriakos Mitsotakis, the Greek Prime Minister, recently announced that the legal framework will be put under scrutiny and changes will be implemented, including the adoption of a re-examined criminal provision. While such an improvement should be encouraged, its importance should not be overstated. It is disappointing that the issue had to come to a head for the legislature to realize that we can no longer afford to sweep sexism and all of its disastrous repercussions under the rug. Also, it goes without saying that the new provision will not have retrospective effect and as a result, countless of cases, including Bekatorou’s, will be decided upon the current, inadequate provisions.

More importantly, although law has a vital role to play in terms of protection, to actually solve the problem, we need to think beyond reformulations of the legal framework and delve deeper into its causes. An important obstacle lies in that the de jure function of the law is often at stark contrast with its de facto implementation. The sad reality is that in Greece, reporting sexual harassment would seem to be an almost impossible task because the actors involved in the process are likely to bring their own biases and criticisms in the proceedings. Such procedural entrenchment against the woman surely explains why such crimes are mostly left unreported.

In this sense, it is illogical to expect law to function properly in a society which is itself part of the problem. The limited power of the law to solve such an issue should thus be acknowledged – ultimately, social actors and their discourses about how the sexes should be treated are as likely to shift norms and behaviors as are legal rules. So, since the roots of the problem are societal and structural, the solution should take a similar direction. The movement emerging in Greece seems to be going towards the right path, but it can be enriched through education initiatives, groups and communities to raise awareness and encourage the unfettered exchange of ideas and views. The first step has been taken. Now, the responsibility to continue what has been started falls on all of us.

*Katerina is a second-year law student at the London School of Economics. She is particularly passionate about family law and conflict of laws issues, eager to introduce a normative perspective in both areas through critical analysis. Recent statutory and case law developments have motivated Katerina to further reflect and contemplate upon the interaction between law and society.

![Filmτατοι [podcast]: Poor Things και Saltburn Filmτατοι](https://atheniantimes.gr/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Filmτατοι-324x235.png)